Dante (May 30, 1265 – September 14, 1321)

This might seem blindingly obvious to anyone who knows my friend and me: I was Cecco d’Ascoli and he was Dante. We’ve had many intersections throughout time and space, and this one painting (above) matches his image in red clothes. (That he wasn’t a Cardinal during this lifetime, might surprise him.)

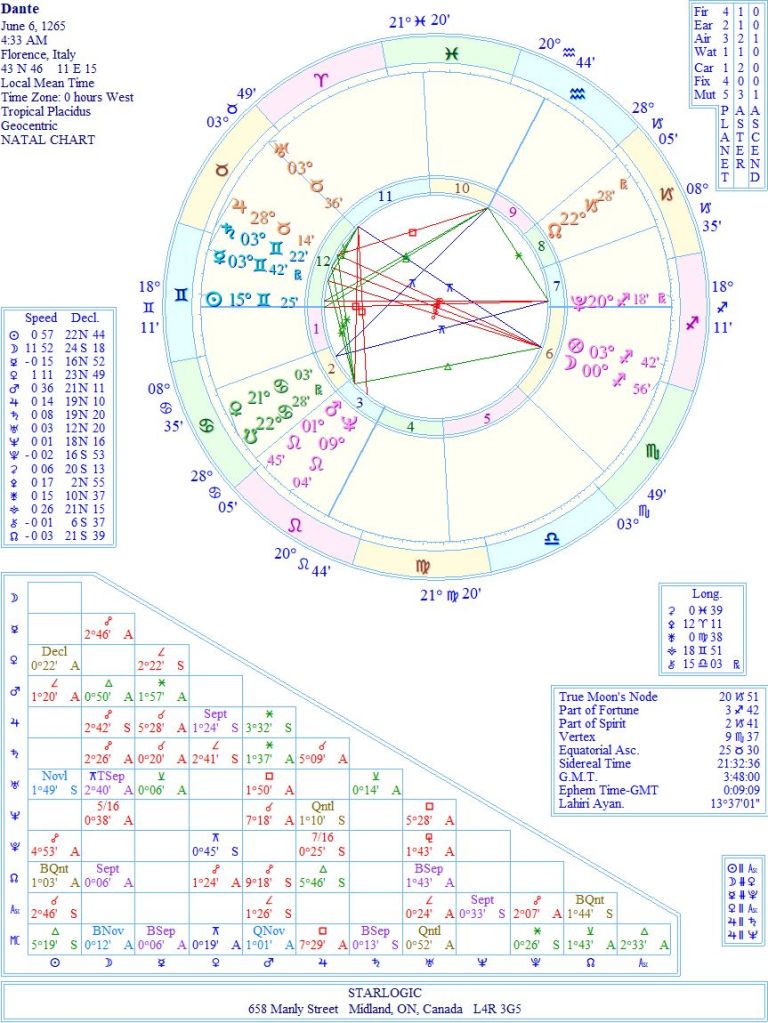

The timing of this chart was probably set for dawn on the day Dante was born. Therefore, we have to take any cojunctions and oppositions to the Ascendant with a grain of salt. Two of the three inconjuncts are independent of a correct timing, but it might be significant that the inconjunct linking Venus and the Midheaven is part of a Yod. Also the Moon inconjunct Uranus needs to be timely, although the 3° before and after the aspect (as dictated by the quick movement of the Moon) looks to be substantially correct.

Moon Inconjunct Uranus

With this aspect you must learn to control sudden outbursts of emotion that occur at difficult times when you least expect it. A particular incident when you were very young may have given you the feeling that you can’t count on anything or anyone for support.

Venus Inconjunct Pluto

You are very concerned about the people you love and find it difficult to leave them alone. Others may think that you are trying to take control or be dominating, but it is simply that when a loved one is hurt, you feel it too. You identify with your loved ones more than most.

Venus Inconjunct Midheaven

This same pattern of thinking may make you believe that you must sacrifice pleasure and enjoyment in order to achieve anything worthwhile in life. Especially as you get older, you should make a conscious effort to find ways to enjoy yourself, be with your friends and loved ones and, at the same time, move toward your goals.

And just to clear up a misconception: I previously linked Dante’s life and death charts with my own birth chart. At the time, I was unaware of Cecco d’Ascoli. His association with Dante is significant.

Ditto.

“When Steiner turns to his own envy, however, he recalls the experience of having bested a writer in a poetry competition, only to have that writer (Steiner does not reveal the name) return from Stockholm with his Nobel Prize and a single insincere word: “sorry.” This is the kind of envy felt by Cecco: the envy experienced by someone who believes in his own superiority and thus believes that another has unjustly usurped the crown which by rights is his own. Cecco’s attacks are not those of a man who considers himself an intellectual inferior; these are hardly the critiques of a man shuddering before greatness. The envy he felt was not that of a mediocrity gazing upon genius. He is not Salieri awestruck before the voice of God incarnate. What emerges from Acerba is a frustration that Dante’s poetic talent ensured that his voice would receive praise, with the result that his intellectual viewpoints, even if flawed, would be accepted by the public. Ironically, it was in this intuition that the astrologer was entirely accurate. Seeing Fortuna as the terrestrial intelligence who works via necessity is hardly an orthodox ideological viewpoint. In fact, the opposite is true. Cecco is far from the only reader whose eyebrows are raised by Inferno VII. The early commentators are extremely uneasy with Dante’s position. Boccaccio treats the passage with kid gloves. Over time, Dante’s shocking stance has come to be regarded as serene. Cecco foresaw this, partially I think because he himself was so seduced by Dante’s poetic skill.” (Fabiab_columbia_0054D_12087)

LikeLike